Most dramatists, playwrights, and screenplay writers agree that many preferred and outstanding stories of all time follow a particular dramatic structure. Your story outline and setting play a significant role, but without a proper structure, it’s incredibly hard to stand out and claim your storytelling prowess.

That’s where Freytag’s Pyramid comes in—to help you pen down strong and compelling poetry, non-fiction, screenplay, or even marketing stories. Your story flows well because you know how to communicate and the perfect structure to adapt when introducing characters, conflicts, turning points, falling instances, and, most importantly, the story ending.

But how is it even possible for amateur and budding writers to master and actualize the Freytag’s Pyramid concept without a detailed understanding of what it’s all about? Without the basics, even an analysis of the films and writings that have leveraged this concept will confuse you further.

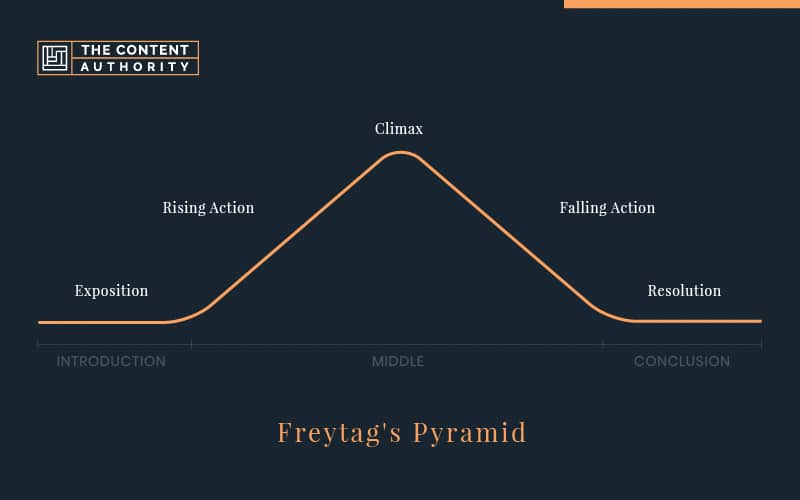

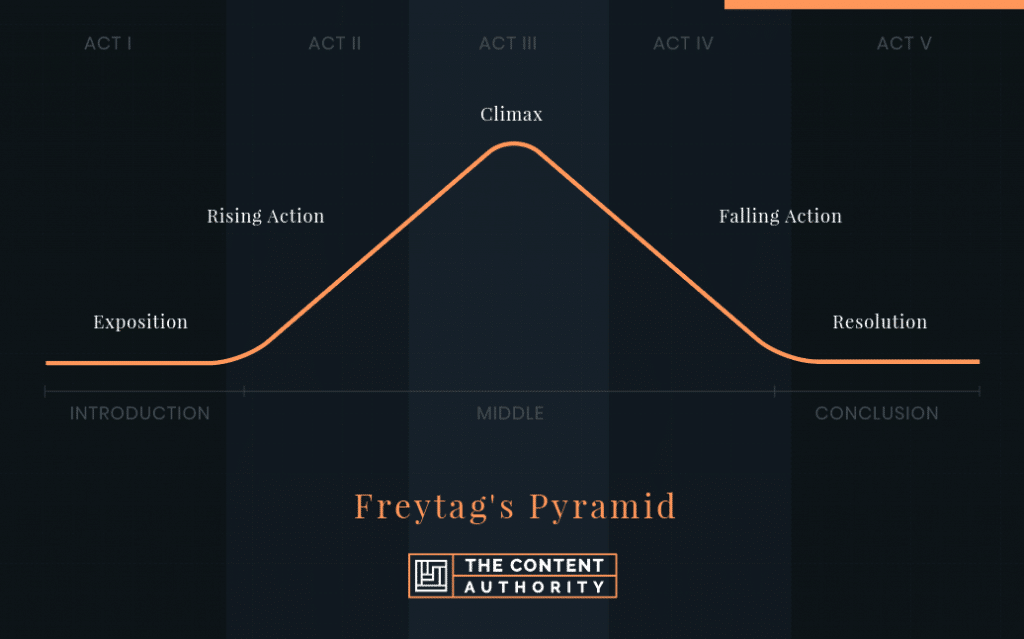

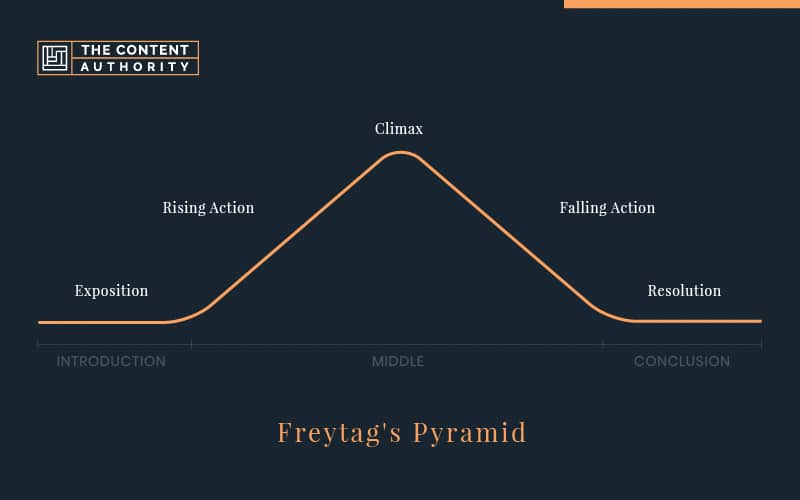

Here are five (5) parts of Freytag’s Pyramid.

- Part 1: Exposition or Introduction

- Part 2: Rising Action

- Part 3: Climax

- Part 4: Falling Action

- Part 5: Catastrophe or Denouement

In this text, we’ll focus on what Freytag’s Pyramid is, Aristotle’s dramatic structure, five parts of Freytag’s Pyramid in depth, and their killer examples. More so, we’ll further look at the popular movies and books to help you practice and apply the Freytag’s Pyramid concept in your story.

Without further ado, let’s fade in!

What Is Freytag’s Pyramid?

Freytag’s Pyramid is an ancient dramatic structure that maps the critical steps to leverage for successful storytelling from inception to the end. Gustav Freytag, a German recognized for playwright work and later a pro novelist in the nineteenth century, devised the dramatic model.

At a time when everybody wants a story that observes a chronological order while events unfold naturally, the ubiquitous structure is now the order of the day in the dramatic world, ranging from writing workshops to lecture rooms. Although it’s not a mandatory approach, most writers embrace it like never before.

A Precise History of Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid dates back to Aristotle. If you’re a historical enthusiast, you’ve probably read a piece or two about the old, wise, and famous Greek philosopher. In one of his outstanding books, Poetics, Aristotle alludes that a plot is the most significant part of every drama, and it consists of three parts.

In his words, “A whole story is what has a beginning and middle and end.” That’s where the fundamentals of dramatic storytelling—three-act structure came into being. While it was meant for tragedies, the structure has found its way in multiple texts (Myers, 2019).

The three-act structure dominated the screenplays until Roman poet and satirist, Horace, explored the idea of five-act structure in one of his poems, the Ars Poetica. The structure found their way in poetry and drama categories.

Later on, in 1863, Gustav Freytag analyzed Aristotle and Shakespearean drama to come up with a masterpiece, the Die Technik des Dramas (Freytag’s Technique of the Drama), which received applause and attention extensively, becoming a point of reference among authors and scholars.

Freytag’s Technique breaks down the three-act model into five elements—the five-act dramatic structure. These elements plot the Freytag’s Triangle, popularly known as the Freytag’s Pyramid or Dramatic Arc (check out more from page 115 of the book).

We’ve talked about Freytag’s Pyramid (from the definition) being a dramatic structure model, right? So, what is this structure all about? Continue reading.

What is a Dramatic Structure?

Dramatic structure is a framework embraced in theatrical work like plays and movies. Aristotle coined the idea of dramatic structure in 335BC, and he has talked much about it in his Poetics. Many scholars (as indicated in the above section) would later analyze the work to come up with various plot structures.

Freytag’s analysis implies that the drama and character groupings occur in two parts, the hero and the antagonist. He describes it as Spiel und Gegenspiel (German for play and counter-play). The climax unites the two different parts to indicate when the action rises and when it falls away.

Uniting the two parts results in a complete dramatic structure, divided into five elements. The five parts, or acts, includes the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and catastrophe. Many of these terms have been used in the modern setting, but with a few changes. For example, “denouement” to stand for catastrophe.

Although the structure augers well with the five-act plays, it remains a literary element (easily modified to suit any narrative). Writers have applied the concept in novels, short stories, marketing, branding, policy campaigns, and much more.

That tells you that dramatic structure is a game-changer when it comes to storytelling. So, why use a dramatic structure? Well, let’s take a look to help you draft your story.

Why Use Dramatic Structure to Shape Your Story

There are multiple plot structures that authors prefer to enact on the narratives. Some love and follow an open and flexible structure while others will always embrace structures with a guiding base, like it’s the case with dramatic structure. Regardless of the approach, you must ensure your story sections and chapters stay connected.

The dramatic structure defines and shapes your story, ensuring there is an appropriate and satisfactory connection of occurrences in the various events and scenes throughout the story. Simply put, the structure Chapter 1 events relate to Chapter 12, depicting a clear and fascinating cause and effect, and more so, action and reaction.

Here are three (3) main reasons you need to use dramatic structure to shape your story. They include:

It’s Easy to Link Events

It can be frustrating when you have fantastic ideas, but you can’t arrange them appropriately into a plot to draft a story with connected scenes and events. The dramatic arc gives your story a satisfying structure and sequence.

It’s because the events appear related; there is active participation, and emotions are well emphasized without unnecessary confusion that makes the story lose its relevance. More emphasis on story and character arcs makes the flow of events effortless.

You Get to Visualize the Story

Your story sounds and looks practical the moment you embrace a visualizing structure. It’s because all the elements are clear. Freytag’s Pyramid gives a structural approach to adopt in every story that you pen down.

How’s that possible? You get to show the chronology of events, visualize falling and rising action, reversals, and turning points in the story. With such an approach, your story shows some significance not just to you but also to the audience.

The Structure Balances Your Plot

A good story needs to be good throughout; no compromise about that. If you have a captivating opening, an ordinary middle section, and a mediocre end, your plot loses some balance. The start, middle, and end need to balance the arcs and trajectories to connect well.

With a dramatic structure, you’re able to build a pro start, like foreshadowing on what will happen later, have some tensions to create some friction at the middle part, and come up with the answer to your riddle as you end your story. With that, you win your audience from an early point.

Here’s the thing. You can’t assume the Freytag’s Pyramid when looking forward to a satisfactory structure and a good story narrative. There is a lot to give your story if you follow the structure.

Below, we’ve comprehensively detailed the five parts of Freytag’s Pyramid to better understand the dramatic structure. More so, to position yourself to an exceptional storytelling framework to leverage in your story.

Who knows? You might be writing the next an Oscar-winning drama or a killer marketing story that converts beyond your expectations. Sounds fulfilling, right?

What Are the 5 Parts of Freytag’s Pyramid?

Back to basics!

If you want to narrate a fantastic story, basics come first. Think about all the contemporary film and television models you’ve watched, from Modern Family to action drama and favorite books. No matter how the authors hide it, they all look formulaic, right? That evidences Freytag’s model. Let’s closely look at each part and complement examples.

Here are five (5) parts of Freytag’s Pyramid.

- Part 1: Exposition or Introduction

- Part 2: Rising Action

- Part 3: Climax

- Part 4: Falling Action

- Part 5: Catastrophe or Denouement

Part 1: Exposition or Introduction

Exposition part also referred to as introduction is the flat line you see at the lowest left side of the pyramid. That tells you that it’s the first movement on the pyramid. Its position and corresponding application on films and books make it easy to identify and understand.

It’s here where the author introduces the characters. The power of every story depends on how an author focuses on the hero (protagonist) and the villain (antagonist). From the major characters, the reader gets to know their relationship and critical information from the start.

The story setting is evident in the introduction. Once you’ve introduced the characters, you place them in an environment that augers well with your story theme, and let them interact fully. Readers find it exciting when they can relate and understand the time and place that major or minor characters revolve.

While interacting within a particular setting, multiple things happen, and that’s where the tone comes out. Emotions follow, creating a mood or atmosphere in the story atmosphere. Conflict introduction enables the story to propel forward.

Exposition begins at Act I (or Scene 1), through the exciting force (the force that allows the protagonist to get into motion). Freytag refers to it as “complication,” and some structures call it the “inciting incident.” Omitting critical details in this part creates loopholes in the story. That’s not good at all.

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Exposition

The Hothouse by the East River is an impressive example to help you understand exposition. The novella, authored by the Scottish short story writer and novelist Muriel Spark showcases characters, story setting and conflict perfectly at the first dramatic arc.

The opening chapter flows quite well, and it’s here you get introduced to Elsa, the protagonist, a German spy, and Elsa’s husband, Paul. From the main characters mentioned and other peripheral characters in various instances, the story begins to reflect at an early stage.

You’ll also notice that at the opening, the author gives a clue of what might bring about the central conflict throughout the story. He talks about Elsa visiting a shoe shop, and the German spy, who intends to kill Paul, fits Elsa’s shoes. Suspicious right?

From the controlled dialogue between Paul and Elsa, we get to know the real picture about their relationship, and that transforms the story atmosphere. The first setting is the shoe shop, but later, the story introduces us to another setting, titular hothouse apartment in New York, where most occurrences take place.

Part 2: Rising Action

The rising action is what you see at the middle left side of the pyramid, slightly above the exposition and before you reach the climax point. It’s the second dramatic arc, with a rising diagonal line that goes towards the climax. Though it’s popularly known as rising action in today’s literature, Freytag refers to it as the “rising movement.”

It’s here where readers start to feel that things are heating up, and as an author, you need to showcase your prowess and capture their attention. The rising tension happens as a result of the conflict. Based on the story, conflicts might be due to an underlying issue like murder, or even propaganda.

Such obstacles rise steadily due to growing complications. That makes the story to shift up the phase, and the reader can notice this with ease. The protagonist doesn’t take in the challenges lightly because most of the happenings hinder them from achieving their core objectives.

It’s important to appreciate that in this stage, any other characters you might not have known get introduced, and they play a critical role in the plot. Typically, characters of less importance, adversaries, and antagonists frustrate further through secondary conflicts, scaling the complications even higher.

The rising action takes Act II (or Scene 2) of the dramatic structure. Simply put, the phase signals the protagonist to act on the central conflict. A lot happens here, and you’ll notice that this part takes much of the narrative space to prepare the audience for the climax. Keeping it even and building the story wins the audience.

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Rising Action

The Stand by Me film directed by Rob Reiner was initially Stephen King’s work, and it features four teenage boys (Gordie, Teddy, Vern and Chris) from Castle Rock, with a mission to find a missing boy who’s presumed dead. It’s one of the best films that showcase the rising action in the story.

It all starts when Vern notifies the other friends about the dead boy 30 miles away. They lie to parents that they’re only on an adventure while their other aim is to find the boy. They join and leave Castle Rock. While on their journey, we start to see things heating up among the boys.

Chopper, the junkyard dogs chase them away from the resting area. Teddy goes into hysteria, and they want him away, Gordie and Chris, who are best friends, get into heated talks. While still on the railroad track, they find themselves in a traumatic state because they’re yet to see the dead body. They keep pushing until they find the body and more challenges follow.

We also get to know about Ace, who’s, in this case, an antagonist. He learns about the body and gangs up with other people, and they’re ready to come for it, and take credit for what the boys have done. That sets in an obstacle and confrontation to the story. Much about Ace and the four boys and what happens next is in the story climax.

Part 3: Climax

The climax takes the highest point of Freytag’s Pyramid. Authors refer to it as “the big moment” in the story. Just like it’s the topmost point in the pyramid, it’s literally and figuratively reflects your story’s highest point. The word climax doesn’t mean the story ends at this third arc, as many think. No, not at all!

It’s instead where events build-up to the top bringing about a turning point. From this point, the story (protagonist situation) takes a transformation, whether for good or worse—nothing remains the same again. It all depends on the tone or theme your story takes.

Freytag’s framework terms it as a reflection point.

Other than being a point of protagonist fate, the climax scenes showcase with the fullest energy the pride, pathos, excellent or ill side, which are among the most significant parts of the story. For instance, most often in comedy, the protagonists experience complications and tremendous obstacles, and in the end, they triumph.

Stories with a tragic approach seem to take the opposite route, because in many of them, as the conflict worsens, things become messy and disastrous for the protagonist. As an author, you have to master the art of writing a climax. If your story doesn’t feel like it has passed through the climax, you’ve probably made a big mistake somewhere.

The climax is a point of profound change and showcasing moments of truth and some suspense, which advances in the next part. According to Freytag, climax carries your story, and even after this point, it reflects what happens next, the counter-play.

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Climax

As You Like It is a popular play by William Shakespeare that was published in the 16th century and features characters in the Forest of Ardenne. It’s one of the most-read stories, with many having read it more than once. Many events follow in the book, but the climax highly evidences Freytag’s Pyramid.

Moments after Duke Frederick chooses to banish Rosalind from the court; she decides to leave for the Forest of Ardenne. Due to the unsafe nature of the places they pass through, Rosalind disguises herself as a man and changes her name to Ganymede. Celia, who accompanies her dresses as a shepherd.

Soon after getting into the forest and settling down, Rosalind, now Ganymede, bumps into the lovesick young men, who have a strong affection towards her. Many characters from Celia, Oliver, Phoebe, Orlando, and Silvius to Oliver Rosalind fall in love, but things do not seem to work.

Now, the turning point, Rosalind goes ahead to reveal her true self. The young men, Phoebe and Orlando, all want to win Rosalind, but the struggle is real. Rosalind is confused with the occurrences; she then plans the marriages for all the parties to ensure there is no disappointment, and everyone gets contented.

Part 4: Falling Action

The falling action sets in after the climax part and describes what happens immediately after that. It’s the fourth dramatic arc, located on the mid of the right side slightly after climax and above the denouement part. It’s clear on the pyramid from the falling line.

As Freytag says, the conclusion should not come as a surprise, and introducing the falling action prepares the audience fully and informs them the story is about to end. However, it doesn’t mean that the audience knows exactly what will happen next or how the protagonist gets along. It’s a strange part with moments of high suspense.

More so, the protagonist and antagonist conflict begin to wind down. Accompanied by some underlying incidents, the protagonist gets to win or lose. In a classical tragic setting, the protagonist’s fortunes reverse only to find themselves in some drama that brings about their downfall.

When it comes to comedy, a protagonist will succeed or improve, leading to great force on the final suspense. In most modern narratives, the protagonist takes a closed move that leaves the audience anticipating heavily for the next action.

Every author needs to come up with a falling action that keeps the reader engaged while slowing down the story without being flat or obvious. Expect some audience to doubt the outcome, but make sure the story events keep them glued to your film or novel.

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Falling Action

The Great Gatsby authored by an American novelist, F. Scott Fitzgerald and published in 1965, is a good example not just to analyze the falling action, but all the five elements of a story that follows Freytag’s Pyramid. However, our focus, for now, is on the falling action.

In the novel, Daisy is in a relationship with two men, Tom and Gatsby. It all starts from the party where Daisy meets his previous lover Gatsby, and they reconcile after many years of separation. Tom previously dated Myrtle, but the relationship had many complications and was now into Daisy like never before.

In one heated summer, Tom and Gatsby bump into each other in the hotel where Daisy was residing. That gets things heating with so much conflict between the two men. Actually, they get into a fight over who needs to take control of the relationships entirely. Well, Daisy leaves them and Gatsby followers her.

Here comes the falling action! Daisy feels so confused about who to settle with following the fight that had transpired earlier. At one point, the confusion makes her crazy, and she drives her car carelessly. Myrtle appears near, thinking it’s Tom with the car, only to be accidentally hit and die instantly.

Part 5: Catastrophe or Resolution

The ending of the story is the moment of catastrophe, as Freytag puts it. From the Freytag’s Pyramid, catastrophe is the lowest right side after the falling action, where the pyramid flattens in a horizontal line. Sometimes, the phase is called the resolution, conclusion, or denouement (the French word for unknotting). The terms alone suggest what’s likely to happen in this part.

Everything gets untied, and the complexities showcased in the plot untangle. These are moments that the reader has been anticipating for quite some time. Here, goals are achieved or not. The same happens for the protagonists. They either succeed or fail. Comedies accompany a moment of failure, but a win in tragedies.

Uncertainties get expounded on, and the reader can now get the real picture. There is also an aspect of conflict resolution and making up as the tension goes down, and characters return to normal life. All this happens due to the introduction of catharsis in the story. A catharsis is an event that eases anxiety and dramatic tension.

You’ll have to wrap everything up well to make your story end nicely. Readers want reassurance, and a good ending will do that. More so, there is a feeling of satisfaction from the story. That doesn’t mean you end as everyone expects, a resounding no. Punish, reward, or soothe characters in a way that the story makes sense.

It’s important to note that Freytag didn’t use the word denouement in his “Freytag’s Technique of the Drama.” It’s a term adopted in modern works to reveal the story’s end. In the dramatic structure, the denouement is a separate scene/act from others.

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Denouement

From Part four (4) of the dramatic structure, we expounded on the falling action by referencing Scott Fitzgerald’s work, the Great Gatsby. The story ends in a way that depicts the relevance of leveraging the Freytag’s Pyramid. It’s easy to notice the denouement part.

After Myrtle’s death, which happened moments when Daisy hit her accidentally with a car, the story nears the end. Gatsby feared that something wrong could happen to Daisy after the incident, and had extreme worries. George, Myrtle’s husband, and Tom Buchanan, who had an affair with Myrtle, decide to take revenge.

Daisy and Tom would later exit the town. Gatsby knows very well that Myrtle’s death was an accident, and Daisy didn’t have prior plans for that. He goes ahead to let everyone know about that. Well, George doesn’t take it well and even blames Gatsby for his wife’s death.

George kills Gatsby and then kills himself. Nick, who sided with Gatsby most of the time, informs everyone about the situation and the burial. On the funeral day, Nick meets Henry, Daisy’s father, and a few people. Surprisingly, the majority didn’t attend the funeral, including Mr. Wolfsheim, a friend and business associate to Gatsby.

Freytag’s Pyramid in Popular Movies & Books

From the ancient Romeo and Juliet (1597) to the fairy latest The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (a 2018 Film), popular movies and books have embraced Freytag’s Pyramid quite well, and you’ll love it.

Freytag’s Pyramid Popular Book: Romeo and Juliet

Part 1: The exposition. Shakespeare’s tragedy showcases the conflict, characters, and story setting. Everything dates back to the 16-17th century at Verona, Italy. The main characters, in this case, are Romeo and Juliet. We’re also introduced to Montagues and the Capulets, whose feud starts conflict in the story.

Part 2: Rising action. Here, Romeo and Juliet’s love goes beyond everyone’s expectations. However, they have to separate (The story complication) because the two families, Montagues, and Capulets, have existing differences. The two decide to beat the odds and marry secretly.

Part 3: The climax. Tybalt kills Romeo’s friend Mercutio after they bump into each other during the ongoing Capulet party alongside other members of the Montague side. That incident hangers Romeo, and he revenges by killing Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt. Romeo goes through a hard time but later finds joy in the fantastic wedding night.

Part 4: Falling action. Juliet’s parents plan to have her married in Paris. But Juliet’s friend helps her to fake death to paralyze the parent plans. More so, they intend to serve Romeo with a note indicating that it’s fake death, and not to mind much. Unfortunately, Romeo doesn’t see the letter. He acquires poison and heads to her tomb, heartbroken, and ready for a suicide mission.

Part 5: Catastrophe or denouement. At Juliet’s tomb, Romeo comes face to face with Paris and Kills him. He later takes his own life. Juliet had taken a sleeping drug to fake death, only to wake up and realize later that Romeo had died. Hungered and confused, she takes her life. It’s then that Capulet and Montague families get to know about their secret marriage and the circumstances that triggered their deaths and decide to reconcile and end the feuds.

Freytag’s Pyramid Popular Movie: The Titanic

Part 1: The exposition. The story introduces the main characters. James Cameron’s classic film features Kate Winslet’s Rose, Cal, Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jack, and other characters. The setting of the movie is on the Atlantic Ocean ship, the Titanic. We also establish Rose’s mother reaction when Rose irritates Cal and how Jack gets to know rose when he saves her from committing suicide. More so, the budding love journey between Jack and Rose.

Part 2: Rising action. Rose spends time with Jack, and it hangers Cal. The two conflicts heavily over Rose. Rose’s mother has already warned her that engaging Jack is not a good idea, and she’ll do anything to stop them. Cal even wants to frame Jack for a crime. Moments later, Rose and Jack overhear the captain warning of a big iceberg. Speeding Titanic hits the icebergs, and things start getting messy.

Part 3: The climax. Now the climactic events start showing. Water continues to sip inside, and this creates extensive tension. The ship bow later goes entirely underwater, and begins sinking deeply. Rose leaves her mother and Cal and goes to rescue Jack, they stop her but in vain. She later jumps on the decks to stay with Jack.

Part 4: Falling action. Jack and Rose are now stranded, worried, and frustrated, and everybody wants lifeboats to save them from freezing water. Rose tries all she can to escape with Jack, who’s in the detention area, but her plan doesn’t work. Jack wants Rose to get into the lifeboats, but Rose insists and wants to accompany him. Though there are many encounters to save Jack, he later dies, and Rose has to take his whistle and get rescued.

Part 5: Catastrophe or denouement. After surviving and finding a way to get rescued—to fulfill the promise he had made to Jack, Rose’s situation changes. She throws away the diamond in the ocean, knowing very well that she dismissed Cal’s marriage hand, and did all she could for Jack. As the screen fades, we see pictures of Rose living a full life and even at some point, embracing Jack. What an ambiguous end!

The Bottom Line: Leverage Freytag’s Pyramid in Your Storytelling

There you go! Freytag’s Pyramid is a solid, easy, and specific dramatic structure to apply in your writing. It helps you to understand every stage of the story. With adequate examples we’ve explained, there is no doubt that dramatic structure can work in your forthcoming story. So, get going!

What are your thoughts about Freytag’s Pyramid? Have you ever tried it? Let’s know how you feel about this five act structure and the frameworks that you’ve used in your writing?

Shawn Manaher is the founder and CEO of The Content Authority. He’s one part content manager, one part writing ninja organizer, and two parts leader of top content creators. You don’t even want to know what he calls pancakes.